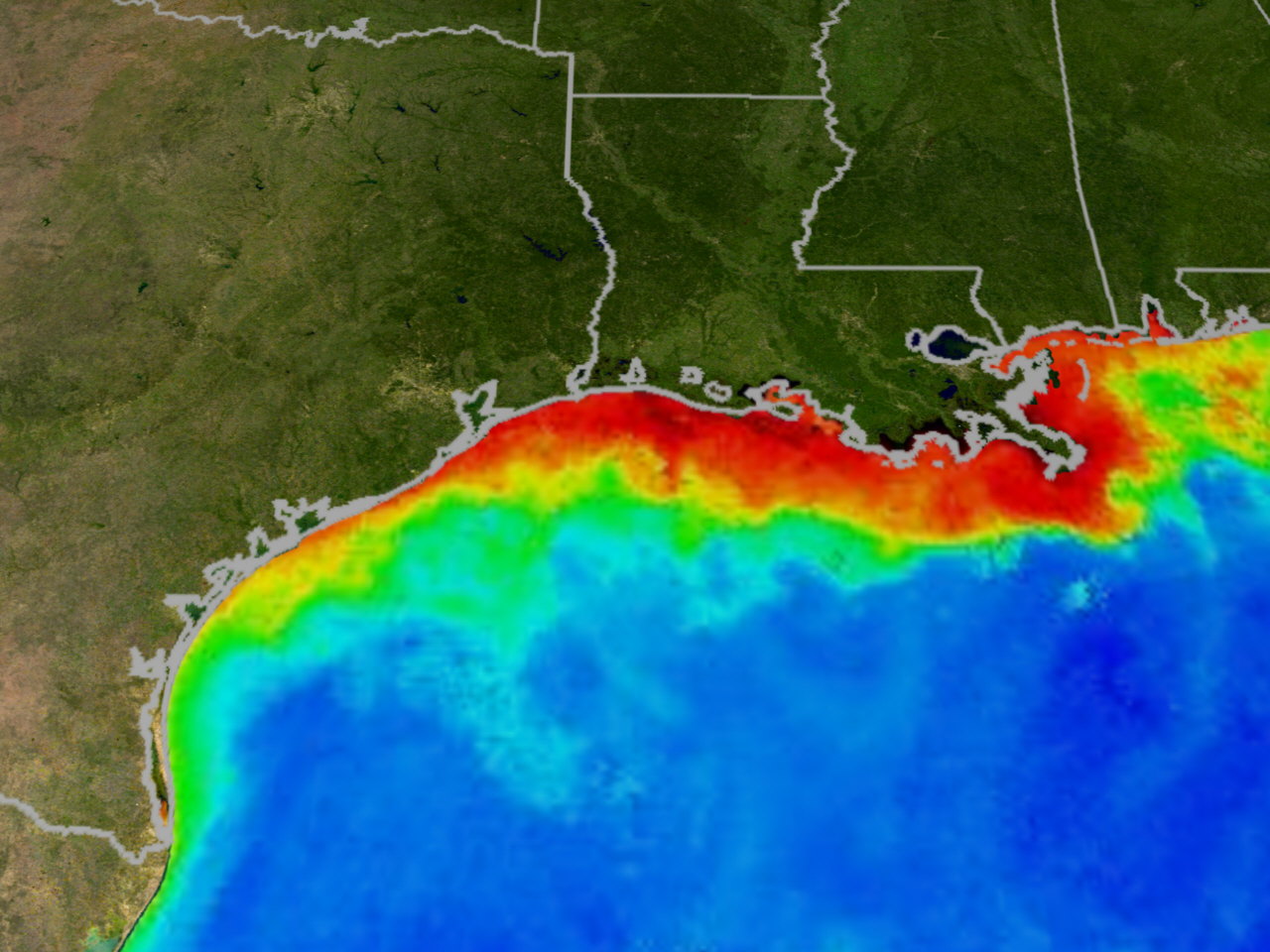

Gulf of Mexico DEAD ZONE caused by agricultural runoff from U.S. farms

08/21/2017 / By Rhonda Johansson

Every year, a hypoxic zone appears along the Gulf of Mexico. Otherwise known as a “dead zone,” it is an area of water that contains little to no oxygen. The significantly reduced levels essentially makes the body of water a biological desert. Hypoxic zones usually occur around summertime. But while these areas are considered to be a natural phenomenon, scientists fear that increased human activity may be contributing to the number of dead zones being observed worldwide. More disturbingly, human factors may also be causing the hypoxic zone in the Gulf of Mexico to grow. Scientists predict that for this year, the hypoxic zone in the area will cover 10,089 square miles. This is about the size of Vermont. Biologists declare that bold and new approaches need to be made now to prevent a biological crisis. They have expressed a desired target reduction of 59 percent in the amount of nitrogen runoffs in the area. This would shrink the hypoxic zone to the size of Delaware.

Approaches to achieve this end are identified in a new study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Researchers from the University of Michigan believe that this goal is achievable, though it would require the adjustment of large scale agricultural practices. The magnitude of the problem prompted an intergovernmental panel to extend the reduction program to 2035. This should give enough time, official spokespeople of the panel say, to achieve the goal of a hypoxic zone with a size of only 1,950 square miles.

What truly causes a hypoxic zone is yet to be fully determined, but scientists believe that the one in the Gulf of Mexico may be due to excessive farmland runoff containing fertilizer and livestock waste. These sources release significant amounts of nitrogen and phosphorous which further contribute to the reduction of oxygen in the water. Thankfully, this is a factor that can be easily addressed with proper management techniques.

Aquatic ecologist Dan Scavia, who was the lead author of the paper, says on Science Daily, “the bottom line is that we will never reach the action plan’s goal of 1,950 square miles until more serious actions are taken to reduce the loss of Midwest fertilizers into the Mississippi River system.”

Scavia noted that for the last 20 years, the average nitrate load dumped into the Gulf of Mexico has not changed, despite the numerous conservation projects made along the Mississippi Basin states. Supposedly, more than $28 billion has been spent in trying to reduce the amount of nitrogen levels. (Related: Ocean Dead Zones Now Top 400.)

“Clearly something more or something different is needed,” Scavia noted. “It matters little if the load-reduction target is 30 percent, 45 percent or 59 percent if insufficient resources are in place to make even modest reductions.”

Some of the proposed solutions are to alter fertilizer application rates, planting cover crops (fast-growing plants which would prevent soil erosion), using alternatives to biofuels, and improving overall nutrient management. What is important, according to the team, is that these solutions be applied methodically and in conjunction with one another. This would introduce an amplified effect, in which both nitrogen and phosphorous levels would be reduced together. This “dual-nutrient strategy” is crucial in achieving a significant nutrient-load reduction.

You can read more stories like this on Environ.news.

Sources include:

Submit a correction >>

Tagged Under:

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author