Toxic ‘forever chemicals’ in farm sludge pose health threats, EPA report finds

01/17/2025 / By Cassie B.

- The EPA warns that sewage sludge used as fertilizer may expose humans to toxic PFAS chemicals, posing serious health risks.

- PFAS in sludge can contaminate crops, livestock and drinking water, and persist in the environment for decades.

- Exposure to PFAS chemicals like PFOA and PFOS is linked to cancer, liver damage, and immune system dysfunction.

- Farmers face contamination crises, with some forced to shut down operations, while states lack consistent regulations.

- Critics urge federal action to regulate PFAS in sludge and prevent further contamination of farmland and water systems.

For decades, American farmers have turned to sewage sludge as a cheap and abundant fertilizer, but a new report from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) warns that this practice may be putting human health at serious risk.

Released on Tuesday, the agency’s draft risk assessment highlights the dangers of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)—toxic “forever chemicals” found in sludge—that can contaminate crops, livestock, and even drinking water. The report underscores the urgent need for regulatory action, yet critics argue the EPA has failed to set enforceable limits, leaving farmers and consumers vulnerable.

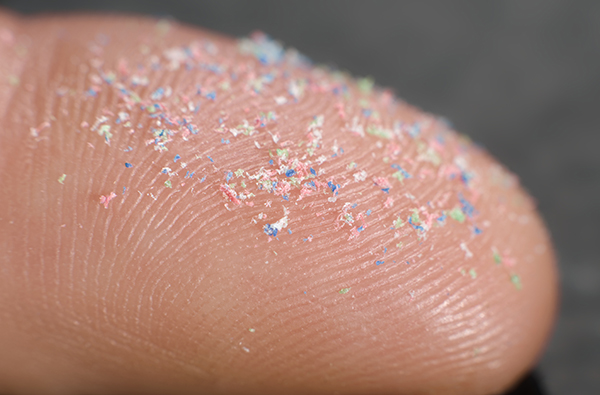

Sewage sludge, a byproduct of wastewater treatment, is often marketed as “biosolids” and spread on farmland as a nutrient-rich soil conditioner. However, the sludge is also a repository for industrial and household chemicals, including PFAS, which are used in products like nonstick cookware, waterproof fabrics, and firefighting foam. These chemicals do not break down in the environment and can persist in soil for decades, leaching into crops, water supplies, and the food chain.

The EPA’s report focuses on two specific PFAS chemicals: perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS). Both have been linked to serious health issues, including kidney and testicular cancer, liver damage, and immune system dysfunction. The agency found that under certain conditions, exposure to these chemicals through contaminated food, water, or soil could exceed acceptable safety thresholds “by several orders of magnitude.”

For example, people who consume milk, eggs, or meat from animals raised on contaminated land face heightened risks. The report also warns that drinking water from wells near farms where sludge has been applied could be a significant exposure pathway.

Farmers left in the lurch

Farmers across the country are already grappling with the consequences. In Maine, dozens of dairy farms have been contaminated by PFAS from sludge spread decades ago, forcing some to shut down operations. In Texas, two farm families filed a lawsuit last year after their land, water, and livestock were allegedly poisoned by tainted sludge applied to a neighboring property.

Despite these alarming cases, the EPA has not set limits on PFAS in sewage sludge, leaving states and farmers to navigate the crisis on their own. Maine is the only state to ban the use of sludge on farmland, while others, like Texas and Oklahoma, are considering similar measures.

“Congress must ensure these farmers aren’t burdened with the costs of fixing this problem – that responsibility should ultimately rest with the polluters,” said David Andrews, acting chief science officer at the Environmental Working Group (EWG).

Federal action is urgently needed

The EPA’s draft assessment is open for public comment for 60 days and could inform future regulatory actions under the Clean Water Act. However, critics argue the agency has been slow to act, even as evidence of PFAS contamination mounts. Last year, the EPA designated PFOA and PFOS as hazardous substances under the Superfund law and set limits for these chemicals in drinking water. Yet, it has not extended similar protections to sewage sludge used in agriculture.

Environmental advocates say the solution lies in preventing PFAS from entering wastewater systems in the first place. This could involve phasing out the use of PFAS in consumer products or requiring manufacturers to treat polluted wastewater before it reaches treatment plants.

The EPA’s report is a reminder of the hidden dangers lurking in America’s farmland. While the agency has taken steps to address PFAS in drinking water, its failure to regulate these toxic chemicals in sewage sludge leaves a gaping hole in public health protections. As farmers and communities grapple with the fallout, the need for comprehensive federal action has never been more urgent. Without it, the cycle of contamination—and its devastating health consequences—will continue unabated.

Sources for this article include:

Submit a correction >>

Tagged Under:

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author