Microplastics in the bloodstream linked to 4.5 times HIGHER stroke and heart attack risk, warn researchers

07/22/2024 / By Zoey Sky

Microplastic pollution in the environment is a worldwide problem with many negative side effects. Several studies have also suggested that once microplastics enter the human body, they can increase the risk of health problems such as heart attack, stroke and even death.

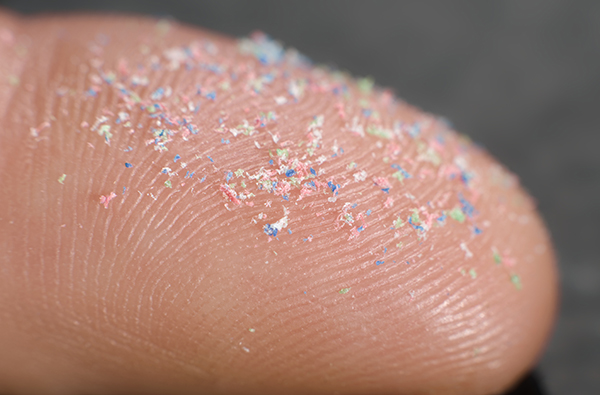

Plastic is a crucial product in industrial production and it is pervasive in daily life. However, when plastic products break down, they turn into microplastics or nanoplastics, which are much smaller. Microplastics are plastic pieces smaller than five millimeters, while nanoplastics measure below one micron (1,000 nanometers).

According to Lin Xiaoxu, a virus specialist with a doctorate in microbiology, everyday plastic products “release” microplastics. Even synthetic textiles shed fiber fragments, and worn-out tires release plastic-containing dust.

Smooth plastic water bottles can also shed microplastics during washing. When these bottles are left out in nature, sunlight and ultraviolet radiation continuously break down the plastics into smaller particles, further contributing to microplastic pollution. (Related: STUDY: Microplastics in the body may aggravate cancer and spur metastasis.)

The following items also contribute to microplastic pollution:

- Bags

- Bottles

- Fishing nets

- Hygiene products

- Particles emitted from factories

- Textiles

- Tire dust

Unfortunately, humans and some animals often ingest some of these particles and other plastic particles accumulate and break down in oceans and soils. Marine organisms such as small fish, shellfish and shrimp, particularly those near coastlines, are more like to ingest harmful microplastics.

Lin explained that the main sources of microplastics are industrial waste and wastewater discharge, which can cause significant environmental damage if left untreated.

Before the wastewater is released from factories, it must undergo thorough processes like biological reactions, chlorination, membrane technology, sand removal, sedimentation, screening and ultraviolet treatment to remove more than 90 percent of microplastics. But complete elimination is not achievable even with modern technology and natural environments may take thousands to tens of thousands of years to fully degrade microplastics.

Health risks linked to microplastics

Microplastics usually enter the body through food and drink ingestion. On the other hand, nanoplastics can be inhaled.

Aside from directly irritating mucous membranes, microplastics can carry environmental microbes like bacteria and viruses into the body.

Lin said once people ingest something toxic, they will often say it can be washed out quickly. However, microplastics are very tiny particles that “adhere to the surface of the stomach.”

He warned that there is no guarantee that washing out microplastics will remove them. He added that the body needs to slowly eliminate them, but this increases “the burden on the body.”

Several studies have revealed that after exposure to ultraviolet light and microbial degradation in the natural environment, “microplastics become more adsorbent, forming complexes with various environmental pollutants on their surfaces, making them more toxic to organisms.”

Microplastics, which function as carriers for dangerous heavy metals and pathogens, exhibit various toxicities upon entering the body.

And while most microplastics ingested through food are excreted via feces, a small portion can remain in the intestines for several days. This can result in inflammation, intestinal damage and the disruption of gut microbiota.

Microplastics can eventually be absorbed into intestinal cells and enter the bloodstream, which can damage organs and systems throughout the body. Organs like the liver and kidneys and bodily systems such as the immune, nervous and reproductive systems are often affected.

The excessive inhalation of microplastics can also result in respiratory tissue damage and disease.

According to a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, most carotid artery plaques contain microplastics. While conducting the study, researchers worked with 257 patients aged 18 to 75 with asymptomatic carotid stenosis.

Researchers detected polyethylene and polyvinyl chloride in the removed carotid artery plaques of 150 patients (58.4 percent) and 31 patients (12.1 percent), respectively.

The research team reported that macrophages within the plaques contained visible foreign particles, some with jagged edges and chlorine content. They added that the patients with detected microplastics had over 4.5 times higher risk of heart attacks, strokes or death compared to the patients without microplastics.

Visit Microplastics.news for more stories about the dangers of exposure to microplastics and how to avoid them.

Watch the video below for more information about the possible origins of microplastics.

This video is from the Finding Genius Podcast channel on Brighteon.com.

More related stories:

STUDY: Researchers found microplastics in all human placenta they tested.

Avoid toxic contaminants like microplastics in salt by switching to Pink Himalayan Salt.

Study: Humans consume over 1,000 microplastics particles every year through TABLE SALT.

Study finds MICROPLASTICS in almost 90% of protein sources, including plant-based ones.

Sources include:

Submit a correction >>

Tagged Under:

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author